This article will look at what is best practise to deal with situations like Muharram 2016, but also the broader socio-political difficulties that they signify, so we can learn lessons for the future. To what extent should Prevent and those affiliated to it be given a standing to provide advice and intervention in both the specific example of Muharram 2016 and the broader socio-political climate? How should leadership at our centres deal with these difficult complexities? To what extent should they have dialogue or take advice from this position? How do they make this difficult, complicated and sensitive assessment and how do we know if they have got the balance wrong?

The previous articles have shown why the incidents surrounding Muharram 2016 cannot be seen as just an isolated localised event triggered by the mistake of local community members, but that they signify the type of pressure put on the Muslim community because of the broader toxic, Islamophobic socio-political climate. Whilst everyone would agree that this climate exists, Muharram 2016 saw a clear division on how to deal with it, especially when specific incidents occur. So, what is best practise when this happens?

In the example of Muharram 2016, the core criticism of Sheikh Sodagar and AIM was that they speak out of turn and therefore attract the type of news coverage that puts the entire community at risk. The assertion becomes, that it is their behaviour that led to the incidents of Muharram 2016 and therefore a different type of behaviour could have avoided it all together.

This raises the following questions;

Should we consider how and what we say given the society and climate that we live in?

Can a different type of behaviour – for example not talking about certain things - stop us from being targeted?

How do we deal with Muslims who come to different answers to us on these questions?

SHOULD WE REALLY SAY THAT?

It seems a simple and obvious conclusion that one should consider the society and climate they are in when deciding what to say or how to behave. Simply put, the comments made by Sheikh Sodagar; specifically the tone and manner in which he discussed an incredibly sensitive topic, got that consideration wrong. Even if one wants to defend his right to expression, or assert that what he was talking about should be discussed in this society and climate, how he said it was not okay. That needs to be made clear, and that lesson needs to be learned.

But a simple conclusion does not answer the complicated questions that Western English-speaking Muslim communities grapple with. For example, how do you discuss homosexuality with your community properly and in a safe environment? How do you promote your content to the rest of the English speaking Muslim world online without making it vulnerable to other hostile actors? How do you know what you say today won’t become unacceptable and controversial in later years resulting in negative press? For example, in the case of Muharram 2016, AIM and ICEL in the UK - who do not generally discuss homosexuality publicly - were caught up in the furore caused by another centre who had asked the same speaker to discuss the topic, in another country, several years earlier. So how can you have a cohesive position when speakers are global but centres are making local decisions on what to discuss?

Nor does a simple conclusion take in to consideration the unfair and discriminatory climate Muslims currently face in the West. What do you do when what you say is unfairly demonised? What do you do when those policing what you say do not have rational or fair criteria? What do you do when the reaction to what you say has a lower threshold than others? Simply put, what do you do when – like many other oppressed minority groups - you are not allowed to make a mistake? To what extent do you accept and comply with these restrictions? How do you know when the line has been crossed?

Most importantly, how should a community behave when its members have different answers to these questions? How do we deal with Muslims who decide to draw the line at a different place? What do we do when Muslims who draw the line at a different place make a mistake? What do you do when those Muslims who make a mistake, don’t react perfectly to when that mistake is misused? Ultimately, the entire debate around Muharram 2016 boils down to these questions.

Firstly, the community should remember that diverse opinion is normal and that everybody has the fundamental right to hold theirs. This of course should be done within the confines of the law, that protects against hate speech and enshrines religious freedom of expression. Sheikh Sodagar’s comments were not illegal. In Muharram 2016, Sheikh Sodagar made a decision his comments were appropriate, others, including this author, believe they were not. But, even if you fundamentally disagree with Sheikh Sodagar, your reaction and behaviour should not ignore the Islamophobic context in which events unfolded. There is a reason why this was something beyond a distasteful remark made in a video published in a small corner of youtube. There is a reason why this was something more than a rigorous, internal, constructive debate about how to discuss homosexuality in the West. You cannot deduct the current Islamophobic climate from the debate. Both the privilege, of those who could have made similar remarks and got away with them, and the discriminatory nature of the exaggerated response to those who cannot get away with it, are real.

HOMOSEXUALITY AND ISLAMOPHOBIA

The topic of homosexuality has put pressure on all traditional faiths in Britain. When same-sex marriage was being debated in the UK, the Church of England resisted, causing a prolonged controversy and media coverage. The Church of England does not currently facilitate same-sex marriages. But there is a stark difference between that media coverage and how Islam’s identical position is dealt with by a press steeped in Islamophobia. Islam’s position on homosexuality is being used as a tool by both far-right and institutional Islamophobia, particularly because it fractures Left wing and liberal support for Muslims. The far-right outlets that cause an outcry over Muslim comments on homosexuality are filled with distasteful homophobic content themselves, yet this doesn’t stop the mainstream media picking up anti-Muslim content from these platforms.

Therefore, it is not just because social norms in Britain are changing that Muslims walk a tightrope on the issue of homosexuality – that would simply put them on par with other faiths - but it is because they have to deal with the additional institutional Islamophobia that pressures, moulds and dictates their behaviour and opinions. It does this by creating an ever-shrinking space of “acceptable Muslim behaviour” – with everything outside that space labelled radicalism, extremism or terrorism.

This is the “creep” the UK’s Independent Terror Legislation Reviewer warned about. For almost two decades, Muslims have increasingly curbed their behaviour under this pressure and it has never been enough. There has – and will always be – more demands made of them. That is the very nature of Institutional Islamophobia that will remain regardless of the behaviour of Muslims. In fact, the more it succeeds in curbing and influencing Muslims, the more it will ask. We must remember this, when we assert that a different type of behaviour would stop Muslims from being targeted.

The aim of Institutional Islamophobia is to create a hostile environment that only tolerates specific state-sanctioned “Muslim opinion” and labels anything outside of that radicalised or extremist. It won’t stop doing this until the entire community has conformed to these rules. Those who deny this is happening are either denying the existence of Institutional Islamophobia or denying how institutional racism has always worked.

Of course there are many people who accept that Institutional Islamophobia exists but believe they have a successful way of navigating it; that is why they will be angry with Sheikh Sodagar in particular for “taking it too far” and disrupting this equilibrium. It is true that if Sheikh Sodagar had not made those particular comments, this particular incident may have been avoided, but on its own it fails to understand how institutional racism actually works.

We can see this by comparing Sheikh Sodagar’s comments on homosexuality with Sheikh Shekaleshfar. Sheikh Sodagar’s comments lacked the understanding of the lived reality of Western Muslims. But what about a few months earlier, when Sheikh Shekaleshfar discussed the same topic carefully, mildly and with nuance and faced a similar fate? The question has actually become whether Islam’s position on homosexuality should be discussed or debated at all or whether there needs to be a complete silence? Or – as Mustafa Field asserts – we should advocate for LGBTQ rights. I will not be opening up that debate here, what I want to highlight is that this sequence – first questioning discussion, then self-censoring discussion and finally advocating for the alternative position – shows Institutional Islamophobia at play. This is how the tightening of the noose will continue and not just on the contentious issue of homosexuality.

Institutional Islamophobia will keep finding ways that Muslims can be called radical, extremists or terrorists

Another example of the same sequence on Institutional Islamophobia is in the discussion on hijab; with top politicians fuelling hysteria over the Burqa. Some Muslims even agree with “banning the burqa” not realising that the demonisation of veiled Muslim women will not stop there, it will move to the style of hijab, to the hijab outright, as it has in other European countries. On these and other issues, Institutional Islamophobia will keep finding ways that Muslims can be called radical, extremists or terrorists to make them vulnerable to racist and Islamophobic legislation.

In response to this we should make smart and considered measures that fully understand the social, cultural and legal framework of the country these measures are being taken, but never allow this institutional racism to victimise anyone, however much we disagree with them.

Correct activism and leadership would have supported and stood by Sheikh Sodagar against the politically-motivated institutional nature of the Islamophobia, despite disagreeing with him. That is not to say they had to stand by the Sheikh’s comments. The two are not mutually exclusive. Instead what has occurred is that parts of the community, and specific leaderships, have picked up the language of Institutional Islamophobia, and specifically Prevent, to continue to sideline a voice they disagree with, using the tools of our collective oppression.

This hurts the entire community, because if this segment of our community being deemed radicalised by its own brothers and sisters is successfully silenced, Institutional Islamophobia will come for its next victim. The Shia community has not been adequately engaged with this danger and has put up a very poor fight to resist it. When the issues of Prevent and radicalisation was focused on our Sunni brothers and sisters, we were not strong enough in our support for them, in fact too often, we asserted that the problem wasn’t “us” it was “them”. Those who were actively resisting Prevent at the time politically and legally warned that this was short-sighted. That soon this would come knocking on our doors too. We were told that would never happen, but here we are today, starting to eat away at our own. Our Sunni brothers were our own, and we did not act. Now, Shia individuals and organisations are in the firing line, and we are still not acting.

That is how we have allowed Prevent legislation to go from extremism being defined as international, criminal, violent terrorism to simply vocal opposition to British values. This process is not going to stop until the job is done.

So, for example, it hurts the entire community, for Sheikh Shomali to send a letter to the Charity Commission that says;

ICEL “share the Commission’s concern that [Sheikh Sodagar’s view] was contentious and inflammatory”, and that “Dr. Shomali did not share any platform with Shaykh Hamza Sodagar” and decided “not to attend the event at all…moreover Dr. Shomali used his good offices to bring pressure to bear upon the Event’s organisers to ensure that Shaykh Hamza Sodagar did not speak at the event again…the trustees wanted to leave no doubt in the minds of the beneficiaries of the Charity [ICEL], as well as Members of the public attending the event, that the Charity [ICEL] did not support the sentiments expressed in the video.”

Responding to a politically motivated letter picked up because of the labelling of these individuals as “radical extremists” in the far-right and tabloid press harms the community. When we give way to Institutional Islamophobia, even passively, we are actually inviting more aggressive behaviour towards all Muslims, because it helps close the space of acceptable behaviour and facilitates the continued pressure on the Muslim community.

It harms our community if centres and leaders endorse the tightening of this space in any way, even if they may personally disagree with the politics, sentiments or actions of the individuals involved. Our centres and leaders should be collectively resisting this tightening of this space.

So for example, in this context, it may not be helpful for Sheikh Shomali to put out a statement with the Camden Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (LGBT) Forum after the Orlando Terror Attack on behalf of the Islamic Centre of England, a move that could be seen as a radical shift in policy, not reflective of his congregation, especially if it helps foster the environment, that people with alternative viewpoints on LGBTQ issues can be termed radicalised or extremist.

I have heard many times the argument that “ICEL is at risk of being shut down if we don’t do these things”. The community should be reassured that many organisations across civil society, including IHRC and CAGE in the Muslim community, politically resist Zionist organisations, state legislation and policy vocally through protest and the courts and have been doing so successfully for decades. They have not been shut down. We shouldn’t be so fearful that we think our Islamic Centre’s will be on the verge of being shut down because of a few far-right news articles or a letter from the Charity Commission.

Also, it is important to note that this letter was not written in coordination with AIM and Sheikh Sodagar, as a united and strategic short-term damage control exercise, alongside a united and coordinated strategy to build a stronger and more resilient community together. Nor was it a temporary measure. Months after it was sent, I was contacted by Hani Al Wardi, a senior member of staff at ICEL, who is seen as Sheikh Shomali’s right hand man. The contact was to invite me to speak at an event at ICEL to mark the Islamic Revolution. It was my first contact with senior staff at ICEL since the Charity Commission letter had leaked. I expressed my concerns about the letter as documented above. Al-Wardi didn’t seem to find any of the actions I was critiquing problematic, instead he asserted that the problem was not the letter itself, but that the letter had been leaked. I expressed surprise at this sentiment. I asked where that leaves journalists and political activists who have a relationship with ICEL. If, for example, I come to the event and later the government decides what I say is problematic and writes a letter to them, will they respond by agreeing to the criticism of me and throw me under the bus too? And would they then assert that the “only problem” in that scenario is if the letter to the government leaked and I found out that they had done this to me? Astonishingly, Al-Hani didn’t deny that this could happen, instead maintaining, that it would be the prerogative of Sheikh Shomali to make such a decision and act accordingly and I didn’t have a right to be aware of it. I explained again why this was hugely problematic and dangerous. I offered to come in to explain to Sheikh Shomali exactly why this was the case – an offer that was never taken up. I also politely declined the offer to speak and explained that I could not cooperate with them whilst they hold such a politically dangerous and damaging policy.

I maintained this position privately over the next year as I continued to hear from community members about worrying behaviour and decision-making that caused increasing political concern. Off the record, young people, including Sheikh Shomali’s students at the Islamic College were confused and concerned about political and social stances that he had expressed privately after he had asked for recordings to be stopped. Most notably these included Sheikh Shomali discouraging political action, as well as calling out “extremists” in the community. On one occasion he told a group of students, we have finished 90% of them off, there is only 10% left.

Unfortunately, during this period, there was a broadening of the narrative of radicalisation behind closed doors, with an unexplained focus on AIM. It is true that Sheikh Shomali and AIM have had professional and personal differences, but that should not turn in to one centre being told that if they host AIM, it would harm ties with ICEL. Another being told that AIM is against Wilayah and shouldn’t be hosted. Or a third being told that AIM are extremists and they will get hassle from the State if they host them.

It is heartbreaking to see the narrative and language of Prevent being used in this way. Our community does not have radicalisation. Our community does not have extremists. Radicalisation and extremism are government policy terms, using them hurts all of us, and puts all of us at risk.

LEARNING FROM THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

This is not a strategy unique to the Muslim community, this has been the State strategy against all minority groups. The struggle for justice in the Black communities in Britain, and especially America, show us clearly that compromising with an institutionally racist narrative bears no fruit, and that the only successful strategy for progress and rights has been resistance against these policies.

Several important comparisons can be made in this regard. In the struggle against institutional racism and state violence against the Black community, we have come to understand that the flaws of the victim are not only insignificant but that highlighting them is a tool of the State to deflect attention away from their systematic oppression and place that burden on to the oppressed. We have come to understand that requiring a threshold of “perfection” from the oppressed is a tool of institutional racism that dictates that the oppressed group are not allowed to make mistakes, or that small mistakes can have dire consequences.

That is why we recognise that when a black man is killed by a police officer and the media focuses on the fact that he was selling unauthorised CD’s outside a shop as in the case of Alton Sterling, or was purchasing skittles in a “suspicious manner” as in the case of Trayvon Martin, they are trying to use racism to smear the victim and make his murder his own fault.

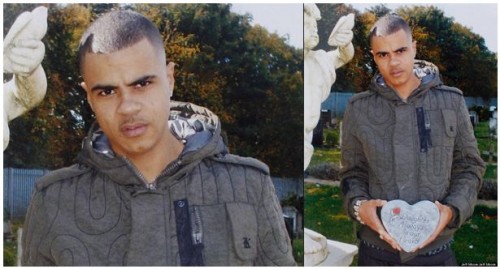

Mark Duggan’s picture was purposefully cropped to make him look thuggish

In Britain, when the police shot dead Mark Duggan, the media used a picture of him looking “angry and dangerous” and called him a thug. What they didn’t say is that they cropped the picture, so you couldn’t see it was actually of a photo of Mark holding a plaque at the cemetery where his daughter is buried. Mark was grieving in that photo. He was not a “black thug” but they purposefully manipulated the photo to make him look like a criminal. The “Independent” Police Complaints Commission told the media that Duggan had shot at police, to later admit this wasn’t true. No Gun was ever found on Mark Duggan.

Because we know these are the victim-blaming tactics of institutional racism, we do not engage or endorse them at all when in this framework. We stand against these character assassinations and these media smears and state clearly that the issue at hand is State racism, not the individual misdemeanours of its victims. That is not to say that the Black community does not work on the issues of drug dealing, or gun possession or even selling illegal CD’s. It is to reject the assertion that these are specific Black phenomena, and be sympathetic of the continued institutionally racist pressure they have to grapple with when trying to create internal progress for their community.

This is a lesson the Muslim community must learn. Highlighting the flaws of the victims of Islamophobia – regardless of their misdemeanours – is a tool of the State to deflect from Institutional Islamophobia and we should play no role in it within that framework. That does not mean we give up on finding space for internal progress. It simply means we never use the tools of Institutional Islamophobia against each other.

The experience of the Black community can also teach us important lessons about whether compromise is a good strategy and what successful leadership fighting these injustices look like.

We did not come to our current understanding of institutional racism and police violence towards the Black community without a long road of resistance. When black men were brutalised and murdered in the ghettos of America, and their communities protested the institutional and systematic nature of that injustice, they were portrayed as violent criminal rioters by the media and politicians. With no voice or agency, they couldn’t galvanise broader public opinion to support them. They were not seen as victims, but were demonised; society was told there was fair law and order, and that black men wouldn’t get killed if they hadn’t been dangerous criminals. But the community didn’t stop resisting.

When those who were clearly not criminals were killed, the community again called out the systemic injustice. The media and the politicians pushed the “few bad apples” narrative, admitting that there may be a few bad cops, but the system is fair. They demonised those who said the system was corrupt. But the community didn’t stop resisting.

With modern technology, video evidence of this brutality became viral. Still victims were demonised, but more and more questions were being asked. Now the narrative became, “well if you had just listened to the instruction of the police officer you wouldn’t have been killed”. But the community didn’t stop resisting.

Black men started putting up their hands to clearly show they were not a threat. And still they got shot. And so started the protest chant “hands up don’t shoot”. As the movement snowballed to gain mainstream support, the resistance maintained that the problem was systemic and held on to their very initial point, that even if someone is a criminal they can’t be killed in cold blood because of racist police. This resistance has pushed many previously “radical” ideas in to mainstream lexicon - today it is common to discuss white privilege and institutional racism and other issues. There was a time, not so long ago, to utter the words meant you were an extreme radical.

Though there is a long way to go, this history has shown what resistance to institutional racism can achieve. It also shows that those who compromised were wrong. Those leaders who focused on the criminality of the victims were wrong, leaders who spoke in the language of the state were wrong.

This story is important. Because it shows that resistance is the method that works, but also that it is not an easy road. Those who called out this oppression from the start were unpopular, were demonised, were called criminals and extremists, but if they had not maintained their stance, the movement would have died at the start. Without them there would be no mainstream movement today. That does not mean they were perfect. It has been a long road of resistance to make the language of the Black civil rights struggle a mainstream lexicon; for terms like Black Lives Matter, White privilege, police brutality to become the norm.

This type of Black civil rights leadership shows us what is impactful and brings about progress. It is not leadership that tows the establishment line, that says the solution is more criminalisation, or places the burden of change on the community. But leadership that calls out State racism publicly, proactively and vocally. In the same stead, for the Muslim community, progress will only come through astute political resistance. Muslim leadership will only be successful if it stands up to the State’s Islamophobic agenda, rather than appease it.

That is why it harms the community, for example, to give a speech, to “discuss issues that the community faces” and discuss only two issues; akhlaq and radicalisation, with no mention of Institutional Islamophobia or government policy. Or that the only mention of government be that “attacking any system, any establishment, any government” is not wise. The community should collectively reject the language and narrative of Prevent, not endorse it from our pulpits.

We have already discussed the comparisons to the Black community, so the words of Martin Luther King are poignant here. Speaking in 1967 in New York, King said:

“As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they asked, and rightly so, “What about Vietnam?” [Today, we could substitute Iraq, Afghanistan or Palestine etc.] They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.”

In this circumstance, it is not even violent resistance that is under discussion, but just basic peaceful political opposition and protest that is being demonised.

This is not the time for withdrawal, this is the time for proactive political resistance. This is the time to give confidence to the community, unite them and mobilise them. At a time when swathes of civil society are resisting Trump, Brexit, Islamophobia, Racism and Tory government policy, we shouldn’t be advocating passive withdrawal.

Muslims in Britain must be proactive in managing their own resistance and allying with others who are resisting. There are plenty of people to ally with. There is currently a groundswell of political resistance against State policy, we shouldn’t choose to withdraw from that and fall in line with the narratives, rhetoric and language of the British government when it is at its weakest and least legitimate moment.

These are complex times in Britain and they require proper insight and understanding. Community leadership must neither downplay the risks nor exaggerate the consequences of resistance. They should also give confidence to their community that though there may be no easy route out when you are a targeted minority, resistance is a difficult but fruitful road.

We should also be resisting to maintain our political spaces in other spheres. As has been documented there is an overlap between this Islamophobia and pro-Zionist lobbying. The space for pro-Palestinian political activism is also being pressured shut.

Pro-Palestinian activists in South Africa

Our centres and figures need to be leading examples in resisting this. For example, it harms the cause when Yousif Al Khoei takes part in an “interfaith” event with the Board of Deputies of British Jews, as Israel is bombing Gaza, and the Board of Deputies is defending their actions. The Board of Deputies of British Jews is staunchly pro-Zionist and increasingly controversial. Amongst many things, they defended Israel in its latest attack on Gaza, they are at the heart of the campaign to make criticism of Israel or Zionism defined as anti-Semitic and even call anti-Zionist Jews anti-Semitic. They are also a main organiser of the anti-Al Quds Day campaign and protest.

Pro-palestinians feel the same about this engagement, as Black South Africans did when Apartheid South Africa was engaged with. The BDS (Boycott, Divest and Sanction) movement has seen a groundswell of mainstream and international support, Muslims should be at the forefront of this, not breaking bread with those who are defending Israel’s illegal and inhumane actions.

There are many anti-Zionist Jews to engage and ally with. If the mainstream interfaith infrastructure does not allow for engagement with anti-Zionist Jews, it should not be engaged with. We have the capacity to create our own interfaith spaces that rejects apartheid and racism, and engages with the many Jews who are against Zionism.

We certainly should not be taking one of the leading Zionist provocateurs in to our mosques and taking “community cohesion” photos with them as Mustafa Field helped coordinate at the Hussainiyat Al-Rasool Al-Adham. The man in question, Joseph Cohen, is known to all pro-Palestinian activists and protesters for regularly bullying and harassing at pro-Palestinian marches and events. This is a man whose has said “anti-Semitism isn’t the problem — anti-Israel/Zionism is.”

Other than in critical and open debate about the injustices taking place in Israel, it hurts the cause of justice to encourage dialogue with Zionists in our mosques on placid issues, in the same way that it hurt South Africans to do so with the advocates and supporters of the Apartheid regime.

For example, when advice is sought on how to deal with their local mosque inviting an openly Zionist Rabbi to speak at an interfaith event, it hurts that cause, to assert that there is no problem with such dialogue and it should be encouraged, as community members were told by Sheikh Shomali.

WHERE TO DRAW THE RED LINE

What we have learned by looking at the struggles of other minority groups in the Western world, is that oppression will never stop asking more of the oppressed. For example, the demands on young black men to “avoid” being killed by police kept increasing and were never “enough” to avoid institutional state racism and violence. They were told don’t be criminals, don’t stand on the street, do as you’re told, put your hands up, don’t speak, but no level of compliance changed the oppression. Compliance does not resolve oppression. Institutional Islamophobia asks the same of Muslims; it will always ask for more however much you give.

Individuals and communities have the right to draw a red line at any point along this journey of demands, because they are all anchored in institutional discrimination. Where red lines are drawn is important, because they signify how much an individual or community is willing to compromise with its oppression. For Muslims, the compromise is between the freedom we should have; to express ourselves, our Muslim identity and our personal opinions and how much we are willing to curb those because of an active agenda against us through state Islamophobia, including Prevent Policy.

The Prevent Policy has been particularly successful in stifling Muslim activism and resistance. Events like Muharram 2016 are significant, not because they highlight that one cleric, once made a mistake in a Q&A in another country many years ago, but because they show how successfully Prevent mentality has infiltrated our community and its leadership.

In Muharram 2016, different groups decided on different red lines in relation to Institutional Islamophobia. AIM, Sheikh Sodagar and others decided they would not compromise on the attack against them at all, regardless of what mistakes may have been made on their end. Sheikh Shomali, Mustafa Field and others decided that it was an occasion for significant compromise. There were others somewhere along that scale. There may well have been a way that could have avoided some of the community fall-out without crossing the red lines of anybody involved, but collectively - by a mixture of mistakes by all parties - this failed to materialise.

The point being made is not to chose one right way from a selection of possible ways, but to illustrate that compromise must have its red lines too and there is a clear way of knowing when they have been crossed.

If you disagree on the particulars of a specific situation; you may think it’s not worth the hassle, it is counterproductive, brings unnecessary attention or simply a silly mistake, however, those you disagree with do not become your enemies. What they have done wrong is not a greater threat than Institutional Islamophobia. Therefore, if how you deal with them overlaps with how Institutional Islamophobia is dealing with them, then a red-line has been crossed. You cannot treat those who refuse to compromise with their oppression as a threat worse than their oppressor. You cannot compromise with your oppressor and show no compromise to your own brothers. You cannot stay silent on Islamophobia and then be vocal against its victims, even if you don’t agree with them. As Martin Luther King said in 1967 you cannot raise your voice against the [actions] of the oppressed without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world; your own government. That did not happen.

In Muharram 2016 that red line was crossed.

The truth is many people and centres in our community have long been either working and cooperating with Prevent or receiving Prevent funding. Historically, Islamic Centre of England has not been one of them, so it is disheartening to see the language and narrative of radicalisation start to be promoted there. This is an uncomfortable truth we must acknowledge and tackle. Even after presenting clear evidence of this funding, some community leaders have been quick to defend. I will only say to them, that you have been long harming our community, and now we are at a point where specific individuals and organisations are at risk. You are hurting your brothers and sisters and putting them in harms way.

Muharram 2016 shows that we are politically unhealthy and unable to resist Institutional Islamophobia.

Political and academic experts in the UK are fundamentally clear on the dangers of Prevent and how to respond to it; as Arun Kundani says, we “should refuse to take part in this…not just private, individual non-participation…but for it to be a broader campaign, so that those individuals being demonised for refusing to take part can find support from a broader movement.”

But where was our broader movement? There was no understanding of the complex political and legal issues at play, no understanding of the British landscape. No ability to recognise that someone like Mustafa Field is a greater risk to our community than someone like Sheikh Sodagar. If we do not understand that, then we have already lost.

This isn’t simply about the removal of Sheikh Sodagar from speaking – perhaps that was necessary, though it should have been done in an entirely coordinated and productive manner. This is about the slow creep of Prevent narrative and language since. Because, even if every criticism ever made about those being deemed “radicalised” is true, it does not justify calling them so.

Unfortunately, despite not being justified, there has been a clear insistence that there is “radicalisation” in our community, and that there is no problem if this labelling overlaps with government legislation or action taken by the British State against the individuals being labelled as such.

I have been able to raise my concerns and points at length in meetings at the Islamic Centre, including with Sheikh Shomali, who was generous enough to give me about 3 hours of his time. We spent the meeting talking about much of the points raised in these articles surrounding Prevent, Institutional Islamophobia, the political landscape, and why it is harmful to the whole community to use the language of Prevent and words like radicals, or radicalised.

However, early in to the conversation, Sheikh Shomali asked for it to be taken off the record (although not confidential).

We couldn’t find common ground in our meeting and what transpired concerned me to the extent that I felt the obligation to write these articles.

These meetings were to facilitate a public platform for these much needed discussions to be held with the community, but this has never transpired.

My sincere message to the community is to please rethink this policy. By saying we have radicalisation, we are inadvertently hurting ourselves and our community. When things like this are said, they cause us harm and danger and invite Islamophobic policies in to our safe spaces. These assertions will be misused by the government; when we acknowledge we are a “problem” this makes us more vulnerable.

We are not a problem. We do not have this problem. We do not have radicalisation in our community. We do not have extremism. We should not use these words on our brothers and sisters. They are one and the same to us; hurting them, hurts ourselves. Harming them, harms ourselves.

I have spent many months speaking to people across this community. Those who have been called radicalised and extremists and those who have started calling others radicalised and extremist. I have seen the hurt that this is causing, the loneliness, the fear. It has broken my heart to hear people called extremist by others who used to be their friends, to be told these people are troublemakers and are dispensable for the greater good. We need to ask ourselves; when did we become this? And when will we stop it from getting any worse? We need to heal this wound. It has not healed and is getting infected.

Our community needs its leaders to take a public and clear stance against Prevent, against our community taking Prevent funding, against the hurtful, dangerous and untrue notion that we have radicalisation in our community, and to be the examples we so desperately need, to resist what is happening to our community.

But it is not just their responsibility, we must all do this collectively. This requires every member of our community to be well-informed on these issues, so they feel confident to tackle them, especially in times like these.

These articles have been my small contribution to this endeavour, that I hope the community will take up seriously.