It can be hard to understand Iran. And even harder to explain it. Especially at a time like this.

There are 80 million Iranians, whose views and news have almost always been packaged, described and analysed in the most reductive way; both inside and outside of the country.

It has often seemed the more reality on the ground has required shades of grey, the more black and white it has been explained away.

Of course, at some point, the oversimplification of these explanations start folding in on themselves, and that certainly feels like the crossroads that Iran – or at least our analysis of it - stands at now.

The sudden protests of the last week could be seen as a sort of perfect storm. But in many ways it is always hurricane season in Iran.

Reading that, your mind might automatically find itself thinking of the dictatorship of the Islamic regime, or the brave protesters fighting for their freedom on the streets.

The truth is, that is just part of the story, from one perspective.

How Brexit Can Help You “Get It”

One of the difficulties of exploring the Iranian landscape is to try and understand the whole tapestry without dismissing one of the many fabrics that make it up.

It isn’t made easy by the fact that Iranians are mostly very passionate and often easily offended, especially when it comes to politics. Trying to understand a view is often seen as endorsing it.

It absolutely isn’t helped by the fact that, in very differing ways, the politics and the media of both inside and outside of Iran overemphasise one piece of the fabric in that tapestry and completely ignore the existence of another.

Nuance is shut down. But that’s what happens when things are explained in black and white.

If you live in the UK or America, that should sound familiar. Ironically, Brexit and Trump can actually help you make sense of things inside Iran.

They are not perfect analogies, but they are useful ones.

For example, how would you explain Brexit to someone who is not British? If you are left-wing and voted to remain, you might say that “in a vie for power the abhorrent Tories promised a referendum voted through by the racism of idiots”.

If you are a working class, rural, Brexiteer, you might say “We are not racist idiots, these elitist Londoners and politicians underestimated us and we took back control”.

Can we pick just one of those statements to explain Britain and British people as a whole?

Can either of these statements even get close to explaining the complexities that led up to Brexit?

Can they take in to consideration the effect of Thatcherism, and New Labour, the lack of industry in the North, unemployment, the recession, budget cuts, using immigration as an excuse for the deficit left by bailouts, the Islamophobia of foreign policy that trickled down to the unemployed white working class, the disenfranchisement of the poor, the young, the polarisation of the media, fake news, fake facts, the impact of social media, UKIP…and the list could still go on.

In the chaos of Brexit, we lost the shades of grey and our landscape became black and white. The feeling of not being able to trust or believe anything, or the feeling of chaos, confusion, and pressure. The polarisation, the lack of objective or nuanced debate. Watching the “experts” and wondering how they became so delusional. These are feelings that we should all be able to relate to by now.

In Iran, the list explaining the complexities of their situation will give Brexit’s a run for its money.

If you try to imagine having to exist in that kind of pressure cooker for a good four or five decades, you might be able to start sympathising with the Iranian plight.

A protester uses her scarf for cover against tear gas

The Pressure Cooker

In Iran any grievances about the government and the regime, are only one ingredient in the pressure cooker. And that is a really important place to start when trying to understand – or help. Especially if you live outside Iran and particularly if you are not Iranian.

In the Western English-speaking world, especially in Britain and America, the position on Iran, from the media and the politicians, is exclusively anchored in regime change and seeped in the history those two countries have with Iran and Iranians.

The much beloved Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh was democratically elected in Iran in 1951. He nationalised Iranian oil from British control (from the company we today call BP). By 1953 he was overthrown in a CIA and MI6 coup d’etat.

The Iranian revolution was an uprising against the UK and US backed Shah (King). And since the revolution, America and Britain have backed Iran’s adversaries at times of war, sanctioned the country and demonised its people.

There is no love lost between the Iranian people and the US and UK establishment. This is a deep-seeded mistrust, and even hate. The overwhelming majority of Iranian people have already established that the UK and America do not have their interests at heart.

The British Prime Minister and the American President may talk about targeting “only the regime” and wanting “the best for the people”, but it is the people who have suffered from their sanctions. From old planes to a lack of medication, it is the Iranian people who have had to constantly live under the looming pressure of sanctions and threat of war. With every country surrounding them invaded by war or military base, it feels like - and is - a closing net on their borders.

That has always been the point of the long game; of sanctions, of slowly suffocating a society, of stifling it, of hindering its progress and growth, of fostering frustration. And then just waiting. That is the point of the pressure cooker.

Imagine having to live under that pressure constantly. To grow up in that, go to school, have your teenage years, your first love, marriage, children, aspirations to own a home, to make something of yourself.

Just a year of political upheaval in Britain and most people were fatigued. Imagine four or five decades.

Imagine, striving through all of this for a semblance of normalcy.

And this point goes not just to the people, but to the Iranian establishment as well. Because actually, Iran has managed, despite the enmity, sanctions and pressure to be a functioning country, even a successful one. No one who has ever visited can say otherwise.

But it is a pressure cooker. And whilst the deep-rooted and profound impacts of the sanctions and hostile policies towards Iran are real, so are bad politicians, bad governance and bad mistakes.

Iran, just like anywhere else in the world, is not immune to those.

Bad Politics

On some level, Iranian politics is not so different than anywhere else.

In Britain you may love or loathe Theresa May or Jeremy Corbyn. You may be Labour and hate Corbyn or Tory and hate May. You may love the Queen or want to get rid of her. You might be passionately pro-Europe or vehemently pro-Brexit. You may be of the many, from all these camps who think mainstream politics is failing – the whole lot of it; Labour, the Tories, parliament and the press.

In Iran too, some people love or loathe Rouhani or Ahmadinejad. Some will die for the Ayatollah Khamenei, and some want him gone. Some love Rouhani but want the Islamic regime gone. Some love the revolution but no longer have trust in Ayatollah Khamenei and want to see another Supreme Leader. And yes, many from all camps think that mainstream politics in Iran is failing.

Here in Britain, however passionately you may advocate or be active for any of these positions, by and large your primary goal isn’t to bring down the collapse of the whole system. Not that those people don’t exist, they do. (I think here in the UK, most people would call them anarchists so it shouldn’t be so shocking if people in Iran call them the same).

In Britain, there is no attempt to try and make out that every protest to save the NHS is actually a group of revolutionaries trying to topple the Queen.

But, this is unfortunately what happens with Iran. And it is not just the Western press, and Iranian opposition activists who do this, but also the establishment inside the country who take this rhetoric, in a way turn it on its head, and use it to shut down legitimate protest.

The unfortunate trajectory in Iran is this; that along the way, the genuine limitations of governing under the pressure of international sanctions have sometimes been used as excuses for bad governance, bad decision making or for one faction to maintain power over another.

This has resulted in a lack of trust amongst some of the electorate, but where and how this mistrust shows itself is different and it is also split down party lines (think about the different answers you would get from a Corbyn and May supporter if they were asked who would destroy the country’s economy).

In Iran, Just think of the potential chaos and confusion, when you can no longer figure out where the impact of the sanctions end and the consequences of bad economic policy begin. When you no longer know whether to believe that your adversaries are waiting on the sidelines to jump on the back of your protest, or if you’re just being told that because the politicians you don’t trust do not want you out on the streets.

The Price Of Eggs

This recent wave of protests seem to have stemmed from the rising price of eggs. Yes, you read that right. It was a mass protest, of mostly poor, mostly pro-revolution, and anti-Rouhani Iranians in Mashhad.

Mashhad is the political strong hold of Ebrahim Raisi, the runner up in the recent presidential race, and the conservative camp that he belongs to has been accused of being behind that initial protest.

The Mashhad protest came on the eve of an annual day of rallies and counter protests that mark the anniversary of pro-regime demonstrations held in the aftermath of the 2009 contested presidential election. These are always a contentious few days in Iran anyway.

The soundness of the decision by the conservatives to get their supporters out on the street at such a sensitive time can definitely be debated.

Senior figures in the Rouhani government had warned that this kind of party political posturing would backfire. They seem to have been proven right when you look at how quickly the protests spiralled out of control, as some Iranians, especially young people, released some of that pent up steam from the pressure cooker.

It is always sombre when Iranians, including police officers and protesters are killed.

This is the tight rope that Iranians; the ordinary citizen and the political leadership have to walk.,

Left-wing and Right-wing politics in Iran

It is also important to understand that in Iran, the left wing and right wing of politics cannot be understood in the same way as in Britain.

In the UK Labour is traditionally left wing in it social policies but also its economic ones and is historically the party of the poor and working class, whilst the Tories have a conservative socio-cultural policy and cater to the rich and elite.

In Iran this definition is split down the middle; the “reformists” like President Rouhani, are liberal in socio-cultural and religious policy but cater to the middle and upper classes and have, what in the UK would be called, a right-wing economic policy.

In general Rouhani has the vote of the young liberals. But not the poor. He has focused on the middle to upper class and cut subsidies for the poorest.

“Hardliners” like former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad are culturally and religiously conservative, but they cater to the working class and poor. Their economic policy is far closer to what would be seen as left wing in the UK, even at times socialist. That’s why Ahmadinejad had popular support in rural areas, but mostly the intellectual class said he was just buying votes by giving the poor subsidies.

To ignore that much of the current unrest is this economic and class battle is to misunderstand what is actually happening.

Pro-regime demonstration on Wed 3 January

English-speaking Iran

On Iran, the voices that reach us in the English speaking world are overwhelmingly, if not exclusively, the voice of the middle to upper class opposition.

That is not to side line that voice. Iranians must work towards acknowledging, respecting and facilitating the entire canvas of voices.

However, what that means is, whilst most Iranian journalists, commentators and experts in the English language have the best interests of their country at heart, they are also, almost always, anchored in a particular position within the landscape of the country.

It would be like saying that every British voice you hear is a journalist, commentator or expert who is also pro-Brexit and campaigns for Brexit in some way or another.

Or perhaps a better example for the UK is to compare it to the political and media analysis we receive about Jeremy Corbyn.

The opinions we receive on Iran are probably as objective and broad as that.

Yet, even Corbyn supporters who can see through the fog on that issue here in Britain, cannot when it comes to Iran.

Commentators like Paul Mason in the UK are well intentioned but miss the mark on Iran. Because it requires the kind of expert – and fair – analysis that simply doesn’t exist.

And this is probably the biggest disservice to Iranians.

Neither calling legitimate grievance anti-Islamic and anti-revolutionary, nor ignoring the millions who support the revolution will work.

Regime Change

Iran is a country made up of many different ilks and a people who continue to hope and strive. They are trying to navigate and enact something better for their society. Just like anywhere else there is push and pull, there are groups who have widely different visions for the future.

Even the most vehement opponent of the Iranian regime is saying we are nowhere near regime change. The reasons for that can be debated. They may assert it is purely and only because of dictatorship and I can only imagine their response to me if I assert that this is not true.

The mistake many Iranian (and non-Iranian) commentators and experts in the English-language make is to anchor the analysis on regime change rather than reality.

When they do this, they can only represent the group of Iranians they belong to; those who want regime change and see what is happening only through the paradigm of how close they are to that goal.

They can only be one piece of fabric in the Iranian Tapestry. They cannot be spokespeople or analysts for the Iranian people as a whole.

If Inside Iran, opposition voices are not given a fair hearing, outside Iran the millions of people who are sincere and passionate supporters of the revolution are made invisible.

Within the increasingly polarised intra-Iranian dialogue there is often rabid name calling (you are a “disgusting ugly, chador-wearing mullah-loving ignorant” or a “un-Islamic, western-loving spy”)

A better way forward for everyone is to agree that there is a spectrum of views and that they need to be respected. This doesn’t solve everything but it is a good place to start.

Once we establish that spectrum; from die hard supporter, those with deep grievance, supporters because of a lack of alternative, those who are simply apathetic, to those wanting a new revolution; we must accept that the majority do not want regime change.

It is a disservice to the ability and intelligence of the Iranian people to think that this regime could really hold them down if the majority wanted them to go tomorrow.

With American and UK policy as it is, the first whiff that the percentage has neared anything close to workable they would come in and enforce the change that they have been spent all these decades fostering.

What Can We Do

As people who are not inside Iran, there is something we can do that can have a profound effect on the Iranian landscape. And that is work hard at removing the ingredients in the pressure cooker that are in our control.

What isn’t being said enough is that if America had not elected a Donald Trump who did not lift the sanction on Iran, perhaps the Rouhani government could implement better what they promised on the economy. The sanctions are real. And they are still there.

If the external pressure on Iran was removed, and Iran was allowed to exist in a space without vultures circling and jumping on any little thing that they can, then we could really start judging the country concretely.

Without the confusion and the guesswork.

We can also acknowledge and demand that ALL Iranians are seen and heard outside of the country. Including the millions who came out in support of the regime on Wednesday and were ignored by the rest of the World.

There are those who would rebut this by excusing away that crowd. But you cannot diminish them to the point of non-existence.

If the argument is that people would chose regime change if they could. Then why not lift the “excuse” the regime have for this closed space?

Why not see what the people do with what is left? How they will shape it and mould it. How far they will take it.

This hasn’t been done because those who are imposing pressure on Iran are worried that, given free reign, in the end, Iranians will just reform and improve what they have into something that would still be unacceptable to the politics of America, the UK, and yes, even some of those Iranians who claim to speak for the majority, whether they are in power or exiled in opposition.

As someone outside of Iran the best help you can give is to put pressure, not on Iran, but on your government to lift the pressure on Iran.

The Last Word To Those In Iran

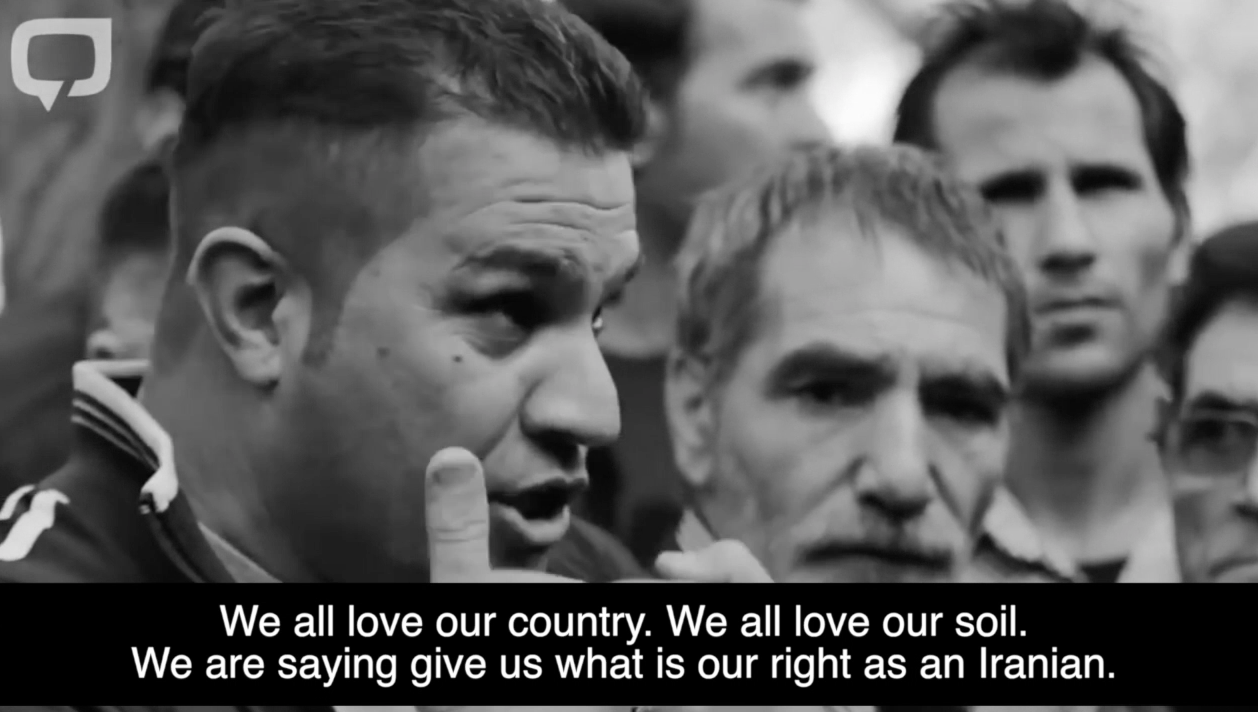

I end with a video I translated in to English, that was posted on an Iranian conservative news website.

It is not to endorse or advocate the view of what is being said here, rather that there is plenty of pro-Rouhani or anti-revolution, or anti-conservative material out there in English, but less of this; the angle of the protests and the disenfranchisement that kick started these protests, that was quickly ignored in favour of the regime change rhetoric.

The views expressed in this video are also representative of swathes of Iranians.

When I watched it, it struck me how similar these grievances are to what I hear at protests in Britain all the time, especially the end about politicians being disconnected from ordinary people.

David Cameron didn’t know the price of a loaf of bread. Surely an Iranian can ask his president to know the price of an egg without the whole world saying that he is calling for regime change.

Ultimately, Iranians will be able to deal with their grievances much better if we stop making them a special case, purely because of our politics and not their protest.